Southern Missionary College in Collegedale, Tennessee was growing. There were students from all over the country, yet they all have one thing in common: None of them are Black. The year is 1965 and Southern students still participate in Confederate/”Dixie” themed events and Black students are not yet welcome. This is the story of Southern’s desegregation.

Read MorePart I: Seventh-day Adventists and the South /

You might think that the first Black students admitted to Southern Adventist University were admitted after the General Conference mandate in 1965.

That’s not the case.

A Black student was amongst the first ever to walk onto campus much before your grandparents were born. Yes, before your great grandparents, too.

Before we answer the question of who that mysterious Black student was, let’s talk about the South. There’s a bit of backstory.

The year was 1892. Most people familiar with Southern’s history will know that to be the very beginning. Back then, the South was a completely different world. Still ravaged after the Civil War and failed Reconstruction, the South was a “mission field,” according to Ellen G. White, Adventist matriarch. Auntie Ellen (I’m using “Auntie” as a term of endearment here) wrote quite a bit about the southern mission field, urging Seventh-day Adventists, a primarily northern religion, to move into the South to begin to teach and preach—setting up sanitariums, schools, publishing houses, and churches.

She urged Adventists to be especially active among Black people—or colored people, as was the lingo of the day:

“But let no Bible-believer think they are doing God service by treating with no contempt one who has a colored skin given them of God. They are not responsible for their colored skin. You reproach God. They cannot change or alter their color [even] if they would. The irreligious are prejudiced against color, and they show their ignorance of God’s mind and His work by showing contempt to the human race because [of] color.”

The South was no friend to a cosmopolitan religion of the North that worshipped on Saturday (Sabbath) instead of Sunday, and supported integration between Blacks and Whites. Auntie Ellen knew she couldn’t possibly advise Adventists to go into the South and knock down every wall:

“And let not, considering the prejudice that exists in the Southern field and with many in the Northern field, the colored field [feel] that the color line shall be obliterated. Should this be managed indiscreetly, it would make the work exceedingly hard to manage, and close the door whereby the help should come to the colored race.”

Newspaper excerpt taken from Dennis Pettibone’s A Century of Challenge: The Story of Southern College 1892-1992

She also warned Adventists going to the South to not be so quick to integrate due to the dangers surrounding them. She warned White Adventists to be rather cautious if they felt chosen to do the work.

Caught working on Sunday? You might get killed by your local community.

Caught inviting a Black person to your church? You might get tarred and feathered by your community.

Caught in church sitting next to Black people? Pack your bags, you may be lynched by your hospitable southern community.

This was the reality of the South.

Auntie Ellen believed that if you were to become a Christian, your prejudice should go out the door:

“Those who are converted among the white people will experience a change in their sentiments. The prejudice which they have inherited and cultivated toward the colored race will die away. They will realize that there is no respect of persons with God. Those who are converted among the colored race will be cleansed from sin, will wear the white robe of Christ’s righteousness, which has been woven in the loom of heaven. Both white and colored people must enter into the path of obedience through the same way.”

Now, where does Southern Adventist University fit in all of this?

A man named Robert M. Kilgore, now known as the “Father of Southern College,” assumed leadership of the Tennessee River Conference—the only organized Adventist conference office in the South in the 1880s and 1890s. He believed Adventists should be setting up schools, sanitariums, publishing houses, and more.

Unfortunately, Kilgore was a northerner. Over 25 years after the Civil War, southerners still did not trust northerners.

Kilgore was a Sabbath-keeping Adventist. There were Sunday laws in the South.

Kilgore advocated for integration, yet he had to recognize that this wonderful ideal was getting in the way of preaching the message to both Blacks and Whites. He didn’t want to follow southern customs of racial separation, but recognized there would be immense difficulty if he had tried to be “too progressive too fast.”

Nevertheless, Graysville Academy was established in Graysville, Tennessee, just thirty miles away from Chattanooga. Kilgore called upon the help of one George W. Colcord. Colcord founded and funded Graysville Academy in 1892. The few Adventists of the South flocked to Graysville for this was the only Adventist school in the entire region.

Southern Adventist University’s original name? Graysville Academy.

Graysville Academy

While Graysville Academy opened its doors to students from far and wide, there was a young woman from rural Mississippi who sought to learn the gospel. After months of sending letters back and forth in correspondence with Seventh-day Adventists, this young woman decided she wanted to be baptized into the church.

This young woman was an anomaly in her family. She began to teach herself how to read and write, eventually corresponding with Seventh-day Adventists. After a few months, she decided she wanted to be baptized into the church. Her people thought she had lost her mind by reading a bit too much. They thought she was a fool.

This woman, from a sharecropper’s family, sold her half of a bale of cotton, and hopped on a train to Chattanooga, Tennessee to go to school and be baptized into the church. Risky, but she felt it was the right thing to do.

Elder and Mrs. L Dyo Chambers

She was welcomed with open arms by two Adventists, a missionary couple, living in Graysville: Mr. and Mrs. L Dyo Chambers.

She was baptized during Christmas week in December 1893 at the end of a week of prayer.

Excitedly, she enrolled in Graysville Academy as a student. Her experience was short-lived:

“I attended classes that day, and in the afternoon a group of first-day citizens [those who worship on Sunday instead of Saturday] of the village came to the principal of the academy [George Colcord] and told him they heard from their children who attended the school that a ‘nigger’ had been admitted to the school. They would not stand for that in Graysville.”

You can imagine the frustration this young woman must have felt when she realized she was the only new student.

She was summoned to Principal Colcord’s office.

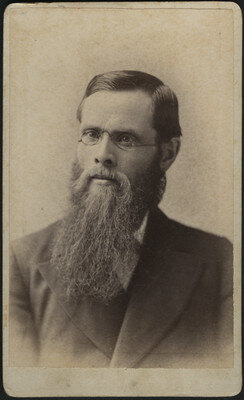

George W. Colcord

Colcord, as you may recall, was the man who funded and founded Graysville Academy. I imagine him sitting behind his desk, stroking his incredibly long beard and adjusting his Harry Potter-esque spectacles as he contemplated his pressing question:

“Young lady, are you a mulatto?”

Phil, what on EARTH is a mulatto?

Mulatto is a bit of a loaded term. Historically, especially into the early twentieth century, it was used to describe those of mixed Black and white ancestry. Oftentimes it’s more specific to be the first-generation offspring of a Black and white person. In this case, our young woman from Mississippi was born to a former slave as a mother and undoubtedly her father was the slave master—a common occurrence in those days. Just ask Sally Hemming, Frederick Douglass, or Booker T. Washington.

By the way, please don’t use this term anymore. It’s often pretty derogatory and insensitive. Most people prefer “biracial,” “multicultural,” or “multiethnic.” When in doubt, just ask!

Colcord must have felt that he needed to ask because the young lady in question was rather fair-skinned. She was, as we say, “white-passing.”

“No, I don’t know what that is—never heard of that before,” she said.

She had no idea what a mulatto was. She’d never heard the term before on her plantation in rural Mississippi, where her family lived in near-poverty and sharecropped for a living.

Colcord was surprised.

“Well, since the people are so angry about you, you’d better wait until I can find out who you are.”

The young woman later wrote in her autobiography:

“I heard no more about that, but I did not go back to school. However, I remained at Graysville, roomed with the matron of the school, helped her with her work, and she taught me privately until the time came for me to return home. I had learned so much in those ten weeks that no one at home dreamed that I had not been to school. I never told any of my people of my disappointment, although it was deep and bitter. I knew it was not the fault of the management of the school or any of the faculty. The members of the church were all very kind to me and made me welcome at the church on Sabbath.” - Mississippi Girl, page 32.

That young woman was Anna Knight, who would become one of the most influential and legendary Seventh-day Adventists. She was not welcome at Graysville Academy because she was biracial. In 1893-1894, she was too Black for the community surrounding her institution. She attended for only one day.

Nurse Anna Knight at Battle Creek Sanitarium

In a world not yet blessed with Oakwood University, Anna was forced to find her education some place else.

Between 1894-1895, Anna returned to Graysville (only to live with her missionary friends) after constant conflict at her home in Mississippi due to her Sabbath-keeping. In December 1894, a man named George. A. Irwin took special interest in Anna. Irwin was a Union veteran of the Civil War, served as President of Ohio Conference, and eventually became President of the General Conference.

“The Chambers [Anna’s missionary friends in Graysville] told him [George Irwin] about me, how I came into the truth and happened to be in their home, that I wanted to go to school, and what had previously happened to me at Graysville. He told them I could go to Mount Vernon Academy, and no questions would be asked. From December [1894] to September [1895], Brother Chambers taught me at night and at odd times during the day trying to prepare me for high school work when I should go to Mount Vernon, Ohio.”

Anna Knight

Throughout her nearly 100 years of life, Anna Knight would return to Chattanooga and Graysville periodically, but never to go back to school. Today, Anna Knight is a celebrated icon all over Oakwood’s campus and her story is well-known among those who study Black Adventism. Unfortunately, at Southern, her short experience is relegated to a single sentence and she is misnamed “Annie.” She is also incorrectly called the first Black nursing professor in 1899. In 1899, Anna was studying nursing in Battle Creek, Michigan and preparing to teach her own people in rural Mississippi before eventually moving to India. Her true story should be told by Southern Adventist University today.

Anna Knight was the last Black Southern student until 1965. Between 1894 and 1965, Adventists of the South subscribed to the racist ideologies and segregationist practices of their communities, forgetting the original counsel of their matriarch, Ellen White, and their mission. They maintained segregation for years to come.

Oakwood Industrial School

Thankfully, a place called Oakwood was established in 1896. Adventists believed that all people deserved an opportunity to learn, especially Black people who were in serious need after the atrocity that was chattel slavery in the United States. Ellen White, a founder of Oakwood, believed in a duty to colored people.

The Morningstar Boat

After visiting both Graysville and Huntsville, Auntie Ellen had this to say in 1904:

“If little things are left uncorrected, there is danger that larger evils will be regarded indifferently.”

Auntie Ellen was right. The little things became bigger, larger things. Greater evils. Segregation at Southern was not corrected for over 70 years.

Auntie Ellen also had plenty to say about Oakwood and Southern before her death in 1915:

“The workers having talent and ability to help must not all congregate in Graysville and leave Huntsville destitute of suitable workers. It is wrong for one place to become strong by leaving others to become weak. To our people in Graysville I would say, be careful not to make Graysville a Jerusalem center. Some of the talent now in Graysville is needed in Huntsville.”

Ellen was trying to warn people to not form an Adventist Jerusalem in Graysville, or Collegedale, where Graysville Academy would eventually move after her death. She asked workers to go and help out Oakwood.

“We found on our visit to Graysville that they are able to carry their own business ably...there is a great deal that needs to be done in Huntsville. They have not had the donation of means or the proportionate talent of capability and determination to make things have a correct showing.”

Ellen knew, again, Oakwood needed more assistance in getting off the ground. All of the talent was going to Graysville (Southern).

“It has been such a mystery to me, I cannot understand it; I cannot unravel it; that is, I cannot see how a community can see—even the community at Graysville, that are so well—situated, and all this—and be so silent and let the thing pass off. I could not sleep; I could not sleep, I could not rest. I thought: If we are not going to come into a position that we shall look out for the interest of our neighbors, it is a shame to any of us by the name of Adventists, to have such a thing go on as has gone on there [Huntsville].”

Ellen lost sleep over Oakwood. She knew that Adventists at Graysville were not helping their neighbors at Oakwood. She thought it was scandalous to be an Adventist in the South and build up Graysville when Oakwood so desperately needed their help.

“Now, God tests us, every one of us, to see what there is in us, and what we will do. He will put an object before us, and He will let that object remain. There is a lesson to be learned...to let a school, or an institution that claims to be a school, go on as has been done, without faithfully rebuking those that are there, is wrong.”

I am interpreting the object placed before us as our racial divide. There is a lesson to be learned. I seek for the students, faculty, staff, and alumni to understand this deeply. There is more to the story of Southern than a “heart problem” with racism. This is historical. It’s embedded. It will not leave until it is faithfully analyzed through time and amended. This is a special duty. It’s bigger than you and me.

In the next section of this series, you’ll find that the Adventist world changed dramatically after Auntie Ellen’s death. The once barren mission field in the South becomes a home to two, separate but not equal hubs, regional conferences are formed, Black administrators replace their white counterparts at Oakwood, southern white Adventists hide behind Auntie Ellen’s Testimonies counsel taken out of historical context, Southern Adventist University does not want to desegregate, and Black Adventists are fed up with racial segregation in their churches, schools, and even hospitals.

The Attorney General of the United States has to get involved.

And it’s not pretty.