“There comes a time when one must take a position that is neither safe, nor politic, nor popular, but he must take it because his conscience tells him it is right.”

I don’t like the way Martin Luther King, Jr. Day is treated. There, I said it.

90 years ago last week, Dr. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia to parents Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King. Growing up in the post-Civil War/failed Reconstruction South, King was subjected to treatment that is easily forgotten by many today. Everywhere Black people looked, there were constant reminders of their “inferiority”. Colored only signs. Ku Klux Klan rallies meant to instill fear. Segregated transportation. Inferior facilities. Separate and unequal schools. Disenfranchisement of Black voters. Discriminatory violence from Whites without any justice from the law.

Society was pro-White in every aspect. The American Dream was seemingly within the grasp of all people, if you weren’t a “Colored Negro,” a poor person, or a woman. The Supreme Court supported institutional and systemic racism in its prior landmark decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, which supported the ideology that Blacks and Whites in the American South should be “separate but equal”. Equality never happened, and especially in the world of the early to mid-twentieth century, it still wasn’t. It wasn’t safe to be Black in the home of the free.

Enter the life of Martin Luther King, Jr.

From childhood, King was humiliated by the treatment of Black people and poor people alike. His early memories included the anger he felt at having to let White people take his seat in buses in the South, even if he had been there first. He recalled moments where he, like others who looked just like him, would have to enter and exit establishments using different entrances than Whites. Black water fountains were often placed lower than their counterparts. If a White man was walking down the street where a Black person was walking, Jim Crow laws mandated that the Black man would then need to vacate the entire sidewalk for their White counterparts. King was angry that he and his people were treated below their human dignity. As he pursued his degree in ministry and his terminal degree in theology, King continually thought of ways to spark his passion for religion and justice into his congregation.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

All men are created equal--if you are White and own property. They are only endowed by their Creator certain unalienable rights (life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), if and only if you are White and own property. This was written during the Revolutionary War, and Black people, from Frederick Douglass to Dr. King, were looking to be included in America’s great declaration and supreme law of the land. It took nearly 200 years.

“If ever America undergoes great revolutions, they will be brought about by the presence of the Black race on the soil of the United States; that is to say, they will owe their origin, not to the equality, but to the inequality of condition.”

By the 1950s, the revolution that Tocqueville predicted over a century before, was primed and ready for action. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka had been passed, declaring, sixty oppressive years later, that separate public schools for Black and White students was unconstitutional. Sixty-four years later, I invited one of the Little Rock Nine (nine Black students who were denied entrance to Little Rock Central High School after the Supreme Court decision), Dr. Terrence Roberts, to my college campus to give a presentation on his part in the budding Civil Rights Movement.

Emmett Till, an African American fifteen-year-old kid from Chicago, had been brutally murdered in Mississippi by White men. At Till’s funeral, his mother kept his casket open for the world to see the brutalities and subhuman treatment of Black people in the South. “Let them see what they did to my baby.” I can only imagine my mother and girlfriend doing that if I were killed in similar fashion.

Meanwhile, in Montgomery, Rosa Parks, a Black woman, refused to get out of her seat for her White counterpart. She went to jail. In response, King took part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, aimed at crippling the transportation system in Alabama and showcasing the economic importance of Blacks in the South. King’s house was bombed, but he pressed on.

We’ll fast-forward ten years to 1965. By this point, Dr. King had received a Nobel Peace Prize, completed the March on Washington and gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, written the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and had participated in nonviolent marches across the country, including the violent Selma, Alabama march. King was not always well-liked during his life, as is what happens when you decide to advocate strongly for an idea. To some, he was “too soft,” as such people felt that he should be advocating for a more militant approach. For others, he was an alleged Communist-sympathizer, which consequently led to the FBI surveilling his actions and wiretapping his phones.

“I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists...little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers...Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

Like many leaders in the tumultuous 1960s, King was assassinated on April 4th, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. To King, the civil rights movement had not concluded, as he began to shift gears to focus more on the plight of poor people. He wanted the country to realize how much it was spending on, in his opinion, copious amounts of money in unneeded military action in Vietnam and put that same energy into serving the poorest of people around them.

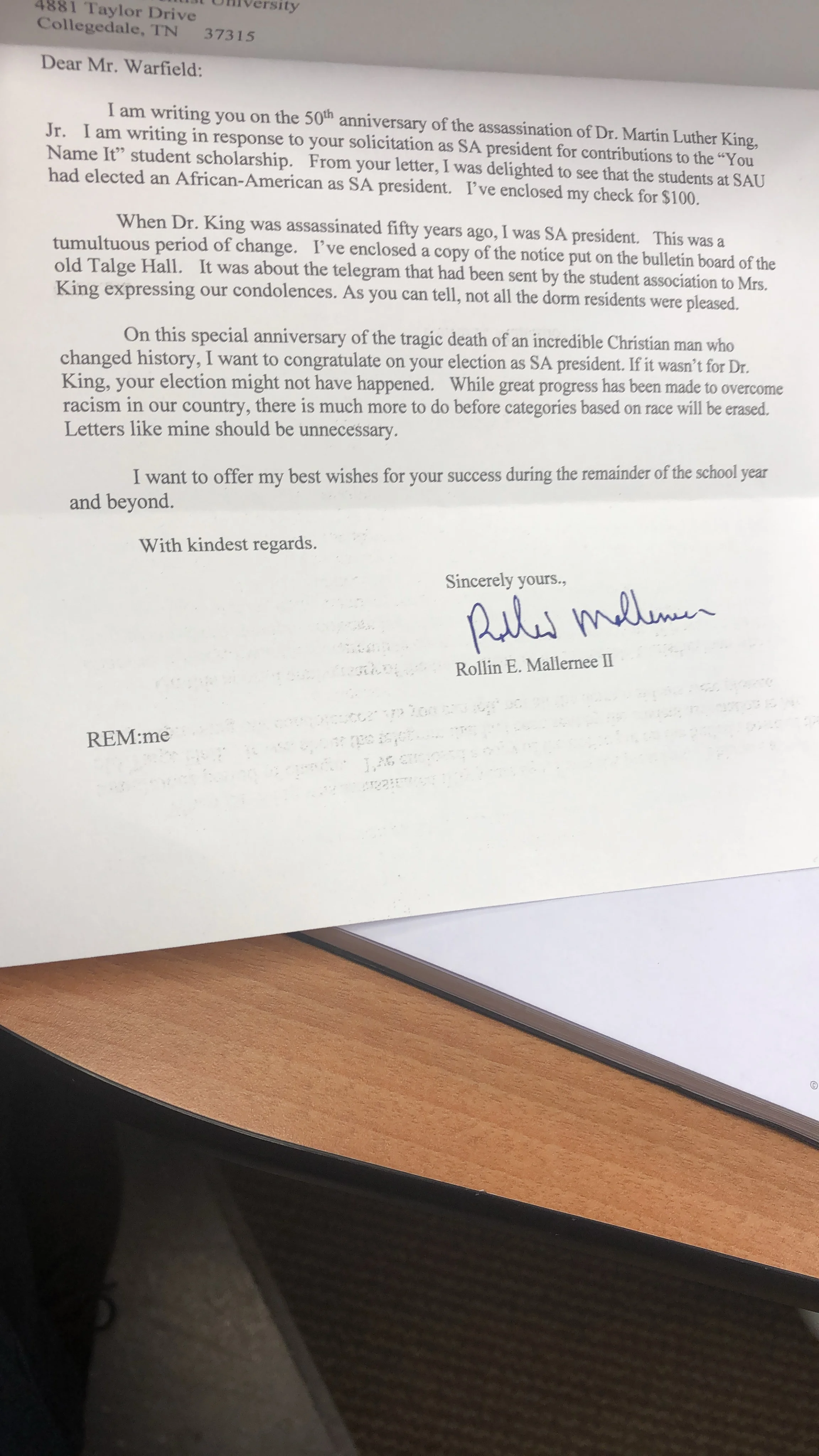

At my school, the Student Association President in 1968 was a controversial figure. He wrote and sent a letter to Coretta Scott King when her husband was assassinated. Posted outside of the men’s dorm, it was defaced by students of an institution still unfortunately perceived by many, for well-documented reasons, as racist. When I was this same institution’s Student Association President fifty years later, my predecessor sent me this letter. I had the privilege of meeting him later that year.

As early as 1971, cities and states were recognizing Dr. King’s birthday as a holiday--a time to remember, celebrate, and continue his legacy. After years of rejection in Congress, despite the support of Presidents like Jimmy Carter, MLK Jr. Day became a reality. By 1983, with heavy pushing from Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, President Ronald Reagan signed Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a federal holiday--the first federal holiday to honor an African American--starting in 1986. Due to the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, Dr. King Day is celebrated on the third Monday of every January instead of his actual birthday, January 15th. Many states resisted the holiday at first, but by 2000, all fifty states had recognized the holiday. Unfortunately, how states recognize this day is where I have a serious problem.

In 2019, Dr. King’s dream is under attack.

It has now been nearly 51 years since Dr. King was assassinated. Coretta Scott King died thirteen years ago. Rosa Parks passed away just months before Coretta. Many of the lawmakers and political figures have been laid to rest (make no mistake, as nearly all of King’s children are still alive, nearly all of the Little Rock Nine are living, and even civil rights figures like Jesse Jackson are still very much alive). Unfortunately, as I peer around the country, it seems as though his legacy will eventually be forgotten. Most importantly, certain politicians use Dr. King’s name to say that they are making change, but that change is rooted in xenophobia, fear, and racism.

Since 1994, Congress designated Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a national day of service. According to the Corporation for National and Community Service, the “MLK Day of Service is observed as a ‘day on, not a day off. [It] is intended to empower individuals, strengthen communities, bridge barriers, create solutions to social problems, and move us closer to Dr. King’s vision of a ‘Beloved Community.’”

I love the idea, but very many institutions are missing the entire scope of what that community service should look like and are even totally renaming the holiday to “National Community Service Day.” They leave the MLK Jr. portion out of it and replace his “controversial” ideas of nonviolence, racial equality, advocacy, and bridge-making with, simply, community service. There is no remembrance of what he stood for.

“I just need to get my service learning credit so I can graduate.” Often, I hear this as I walk around my campus. I think some of us have missed the target.

At my university near Chattanooga, Tennessee, we have a prime opportunity to do more than embark on a mad rush to do, solely, community service. Atlanta, the home of the King Center, is just two hours away. Montgomery, home of the Civil Rights Memorial Center and so much more, is three hours away. Birmingham, the site of 16th Street Baptist Church where four Black girls were killed by Klansmen, is two hours away. Memphis, home of the National Civil Rights Museum and Dr. King’s assassination, is 5 hours away. There are opportunities to learn more about King and the Civil Rights Movement, especially in the Deep South. We must take advantage of these opportunities, knowing the volatile history and perception of our institution. There is an indoctrination that must happen. We could be the leading institution who believes not only in community service like everyone else, but also the educating of the future generation. We must become King’s Dream. If that 90-year-old man were alive today, I’m sure he’d find some way to tell all of us that there is still so much work to do. First, we must learn. Then, we must dream. Finally, we must DO.

To those who think some of us want too much too fast, this is what Dr. King wrote as he sat in a closet of a jail cell in Birmingham:

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action’; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a ‘more convenient season.’” - Letter from Birmingham Jail

Sometimes, in order to make change, you must be willing to do what is controversial. Revolutions are not inherently militant. To my White friends, understand that many of us have been told, “No, not yet” for so long. “Not yet” oftentimes becomes never. I’m sure President Barack Obama was told “First Black President? Not yet.” I’m sure Michael Jackson was told “Greatest entertainer and greatest selling album of all time? You’re Black and you’re too idealistic, not yet.” I’m sure LeBron James has been told “Outspoken Black athlete? Not yet. Shut up and dribble.”

Don’t let it stop you.

Yes, Dr. King lived a life of service. He lived a life of service to his community, but that service was in uprooting the inherently racist and social norms in a society that promised life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all people. When Americans remember Dr. King, it should not be mistaken and equated solely with the idea of picking up trash, singing to people, or building new structures for those in need. Understand that there is absolutely nothing wrong with those things, but declaring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as “National Community Service Day” for years to come may miss the entire point of what King lived and died for. Coretta Scott King did not advocate so hard for a community service day. Stevie Wonder did not write an iconic birthday song solely for your Black friends to sing and dance to at their birthday parties.

I plea with you to go research and understand why you might decide to participate in this weekend’s community service or decide to spend some time learning at various civil rights museums around you. Books are available, articles are accessible, and speeches are applicable.

Coretta Scott King said it best herself: “The greatest birthday gift my husband could receive is if people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds celebrated the day by performing individual acts of kindness through service to others."

Don’t do community service if you don’t understand the dream.

Don’t take the day off.

I pray Dr. King’s dream comes to fruition and politicians shall not damage his legacy by proclaiming the opposite of what he stood for. I pray leaders everywhere will not overwrite this day with only community service.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life—longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will…. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”